In 2012, at age 60, I was told I was prediabetic. I had suffered a failed knee surgery, which lead to 2 years of rehab and modest activity. The reduced activity was harming me further, because the odds are that my prediabetes will turn to diabetes within 10 years.

In 2012, at age 60, I was told I was prediabetic. I had suffered a failed knee surgery, which lead to 2 years of rehab and modest activity. The reduced activity was harming me further, because the odds are that my prediabetes will turn to diabetes within 10 years.

Despite everything I changed in my lifestyle, I remained prediabetic. During these past 2 years, I kept my weight down (BMI = 19), did strength training 3 or more days per week, and did 30 minutes of exercise almost everyday. I also took a prediabetes class, and I stuck to the desired model of proportions for a dinner plate: 1/2 salad & veggies, 1/4 fruit & starch, and 1/4 protein. The endocrinologist scheduled my A1C to be checked every 6 months.

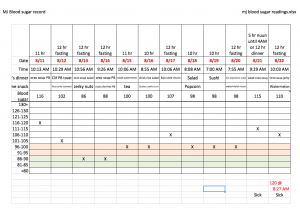

To me, checking my blood sugar every 6 months was not granular enough. I wanted to know a lot sooner if anything I tried was having an effect. My sympathetic internist prescribed an Accu-Chek Compact Plus blood glucose meter, and for most of the past several months I measured my morning blood glucose (BG) daily. I also started counting carbs. Unfortunately, just as I was able to get my morning BG in the 90-100 range, I caught a respiratory infection that lasted over 4 weeks. My BG shot up to 110-120 and even though my chest is finally clear, my BG still hasn’t gone back down.

While I haven’t achieved my goal of reversing my prediabetes, here’s what I’ve learned about my body’s metabolism:

- I can’t afford to eat late at night. I always assumed that if I went to bed with a full stomach, my body would digest it while I was sleeping. But my endocrinologist says that your pancreas stops secreting insulin while you’re asleep. So if I finish eating dinner and dessert at 10:00 PM, my BG will be >120 in the morning, even 10-12 hours after I last ate. I changed my lifestyle (don’t always succeed) to finish eating dinner no later than 8:00 PM. A side effect of this was that I lost 3 lbs in one week. Now, 3 lbs doesn’t sound like much, but that’s almost 3% of my body weight.

- Besides sticking to the properly proportioned dinner plate, it’s also important to count carbs. My morning BG will shoot up 20 points if I eat a carb-heavy dinner with beans and rice. Or eat one of those scrumptious 4″ chocolate chip treats from the x-rated Hot Cookie in San Francisco’s Castro District. Or eat a bag of kettle corn at a San Jose Earthquakes evening game. I never made the mental carb connection until I correlated my AM BG with the previous evening’s consumption. After that, I now read nutrition labels and I check carbs on the most common things I eat.

- It’s easy to do this – just google the food and the word “carbs”. E.g., look up the carb content of an apple by googling “apple carbs”. I now try to keep a meal at 45-80 carbs and a snack at 15 carbs.

- I used to workout on an empty stomach, because otherwise I would have regurgitation while running around. However, this mini-fasting also raises my BG because my liver breaks down glycogen to produce glucose when there isn’t enough in the blood stream.

- I did a lot of research before selecting the Accu-Check Compact Plus meter. When it comes to making myself bleed, I’m a wuss. The lancet mechanism on this meter makes that task pretty easy. However, the cost of daily self-testing is shocking. With insurance coverage, each test strip costs me about $1. Without insurance, the retail cost of the strips is $3. Plus the meter, lancets, alcohol swabs, and control solutions add up. With the high rate of diabetes, and the high percentage of Americans without health insurance, how will uninsured diabetics control their disease?

- While the meter is pretty easy to use, the hardest part was getting the finger prick right. In the beginning, I probably wasted 20 strips because I couldn’t get a large enough drop of blood fast enough. My best tip here is squeeze out the blood first, and then turn the meter on.

- It turns out that meters are only accurate within 10%. Part of the problem is that untrained consumers are not as precise as lab technicians. But you also find that different fingers can vary by 10 points! And if your fingers are cold, it can take longer to get the interstitial blood out, leading to high results. So get consistent in your technique, if you want your readings to be meaningful.

- In Sep-2014, researchers reported that artificial sweeteners (pink saccharin Sweet N Low, yellow Splenda sucralose, and blue Equal aspartame) increased glucose intolerance in mice because the sweeteners reduced the beneficial bacteria (microbiome) in the gut. They also found disrupted BGs in non-diabetic humans who were given saccharin for 6 days. And further, injecting gut bacteria from these human subjects into the mice also gave the mice glucose-intolerance.

- Stanford internist Dr Bryant Lin gave a health talk on Oct-2-2014, where he admitted that he stopped using sweeteners after he read the research.

- I had been consuming about 7 servings/day of Splenda and stopped in favor of a small bit of honey, hoping to naturally repopulate my gut. But it doesn’t seem to be working for me…

- I’m glad I started self-testing BG. For one thing, I now know I really don’t want to get diabetes and have to prick my fingers like this for the rest of my life. Ouch!

- When I reported my observations on the effect of carb-heavy meals, the endocrinologist said to me, “Well, I could have told you that.” But you know, he didn’t. And that’s why I believe that studying, researching, and trying a few things on your own is the best way to understand how your body works.

Hope you found this helpful!